Free Love on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Free love is a social movement that accepts all forms of

.

According to feminist critique, a married woman was solely a wife and mother, denying her the opportunity to pursue other occupations; sometimes this was legislated, as with bans on married women and mothers being employed as

A number of utopian social movements throughout history have shared a vision of free love. The all-male

A number of utopian social movements throughout history have shared a vision of free love. The all-male

The ideals of free love found their champion in one of the earliest English

The ideals of free love found their champion in one of the earliest English  A member of Wollstonecraft's circle of notable radical intellectuals in England was the Romantic poet

A member of Wollstonecraft's circle of notable radical intellectuals in England was the Romantic poet

Free love began to coalesce into a movement in the mid to late 19th century. The term was coined by the Christian socialist writer

Free love began to coalesce into a movement in the mid to late 19th century. The term was coined by the Christian socialist writer  The women's movement, free love and

The women's movement, free love and

love

Love encompasses a range of strong and positive emotional and mental states, from the most sublime virtue or good habit, the deepest interpersonal affection, to the simplest pleasure. An example of this range of meanings is that the love o ...

. The movement's initial goal was to separate the state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

from sexual and romantic matters such as marriage

Marriage, also called matrimony or wedlock, is a culturally and often legally recognized union between people called spouses. It establishes rights and obligations between them, as well as between them and their children, and between ...

, birth control, and adultery

Adultery (from Latin ''adulterium'') is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal ...

. It stated that such issues were the concern of the people involved and no one else. The movement began around the 19th century, and was advanced by hippies during the Sixties

File:1960s montage.png, Clockwise from top left: U.S. soldiers during the Vietnam War; the Beatles led the British Invasion of the U.S. music market; a half-a-million people participate in the Woodstock, 1969 Woodstock Festival; Neil Armstrong ...

.

Principles

Much of the free love tradition reflects aliberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

philosophy that seeks freedom from state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

regulation and church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* C ...

interference in personal relationships. According to this concept, the free union

A free union is a romantic union between two or more persons without legal or religious recognition or regulation.

The term has been used since the late 19th century to describe a relationship into which all parties enter, remain, and depart ...

s of adults (or persons at or above the age of consent) are legitimate relations which should be respected by all third parties whether they are emotional or sexual relations. In addition, some free love writing has argued that both men and women have the right to sexual pleasure without social or legal restraints. In the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edwardia ...

, this was a radical notion. Later, a new theme developed, linking free love with radical social change, and depicting it as a harbinger

A harbinger is a forerunner or forewarning, but may also refer to:

Companies

* Harbinger Corp., an Internet-oriented business

* Harbinger Capital, a hedge fund

* Harbinger Knowledge Products, an eLearning products and content services compan ...

of a new anti-authoritarian

Anti-authoritarianism is opposition to authoritarianism, which is defined as "a form of social organisation characterised by submission to authority", "favoring complete obedience or subjection to authority as opposed to individual freedom" an ...

, anti-repressive sensibility.

According to the modern stereotype, earlier middle-class Americans wanted the home to be a place of stability in an uncertain world. To this mentality are attributed strongly-defined gender roles, which led to a minority reaction in the form of the free-love movement.Spurlock, John C. Free Love Marriage and Middle-Class Radicalism in America. New York: New York UP, 1988.

While the phrase ''free love'' is often associated with promiscuity in the popular imagination, especially in reference to the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s, historically the free-love movement has not advocated multiple sexual partners or short-term sexual relationships. Rather, it has argued that sexual relations that are freely entered into should not be regulated by law, and may be initiated or terminated by the parties involved at will.

The term "sex radical" is often used interchangeably with the term "free lover". By whatever name, advocates had two strong beliefs: opposition to the idea of forced sexual activity in a relationship and advocacy for a woman to use her body in any way that she pleases.Passet, Joanne E. Sex Radicals and the Quest for Women's Equality. Chicago, IL: U of Illinois P, 2003.

Laws of particular concern to free love movements have included those that prevent an unmarried couple from living together, and those that regulate :adultery and :divorce, as well as :age of consent, :birth control, :homosexuality, :abortion, and sometimes :prostitution; although not all free-love advocates agree on these issues. The abrogation of individual rights in marriage is also a concern—for example, some jurisdictions do not recognize spousal rape

Marital rape or spousal rape is the act of sexual intercourse with one's spouse without the spouse's consent. The lack of consent is the essential element and need not involve physical violence. Marital rape is considered a form of domestic vi ...

, or they treat it less seriously than non-spousal rape. Free-love movements since the 19th century have also defended the right to publicly discuss sexuality and have battled obscenity laws.

Relationship to feminism

The history of free love is entwined with the history offeminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male po ...

. From the late 18th century, leading feminists, such as Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (, ; 27 April 1759 – 10 September 1797) was a British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional personal relationsh ...

, have challenged the institution of marriage, and many have advocated its abolition.Kreis, Steven. "Mary Wollstonecraft, 1759–1797". The History Guide. 23 November 2009 teacher

A teacher, also called a schoolteacher or formally an educator, is a person who helps students to acquire knowledge, competence, or virtue, via the practice of teaching.

''Informally'' the role of teacher may be taken on by anyone (e.g. whe ...

s. In 1855, free love advocate Mary Gove Nichols

Mary Sargeant Gove Nichols (; August 10, 1810 – May 30, 1884), also known by her pen name Mary Orme, was an American women's rights and health reform advocate, hydrotherapist, vegetarian and writer.Iacobbo, Karen; Iacobbo, Michael. (2004). ''Ve ...

(1810–1884) described marriage as the "annihilation of woman", explaining that women were considered to be men's property in law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

and public sentiment, making it possible for tyrannical men to deprive their wives of all freedom. Full text at Internet Archive (archive.org). For example, the law often allowed a husband to beat his wife. Free-love advocates argued that many children were born into unloving marriages out of compulsion, but should instead be the result of choice and affection—yet children born out of wedlock did not have the same rights as children with married parents.

In 1857, in the ''Social Revolutionist'', Minerva Putnam complained that "in the discussion of free love, no woman has attempted to give her views on the subject" and challenged every woman reader to "rise in the dignity of her nature and declare herself free."

In the 19th century at least six books endorsed the concept of free love, all of which were written by men. However of the four major free-love periodicals following the U. S. civil war, half had female editors. Mary Gove Nichols

Mary Sargeant Gove Nichols (; August 10, 1810 – May 30, 1884), also known by her pen name Mary Orme, was an American women's rights and health reform advocate, hydrotherapist, vegetarian and writer.Iacobbo, Karen; Iacobbo, Michael. (2004). ''Ve ...

was the leading female advocate and the woman most looked up to in the free-love movement. Her autobiography (''Mary Lyndon: Or, Revelations of a Life: An Autobiography'', 1860) became the first argument against marriage written from a woman's point of view.Spurlock, John. "A Masculine View of Women's Freedom: Free Love in the Nineteenth Century." International Social Science Review 69.3/4 (1994): 34–45. Print.

To proponents of free love, the act of sex was not just about reproduction. Access to birth control was considered a means to women's independence, and leading birth-control activists also embraced free love. Sexual radicals remained focused on their attempts to uphold a woman's right to control her body and to freely discuss issues such as contraception

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

, marital-sex abuse (emotional and physical), and sexual education. These people believed that by talking about female sexuality, they would help empower women. To help achieve this goal, such radical thinkers relied on the written word, books, pamphlets, and periodicals, and by these means the movement was sustained for over fifty years, spreading the message of free love all over the United States.

History

Early precedents

A number of utopian social movements throughout history have shared a vision of free love. The all-male

A number of utopian social movements throughout history have shared a vision of free love. The all-male Essenes

The Essenes (; Hebrew: , ''Isiyim''; Greek: Ἐσσηνοί, Ἐσσαῖοι, or Ὀσσαῖοι, ''Essenoi, Essaioi, Ossaioi'') were a mystic Jewish sect during the Second Temple period that flourished from the 2nd century BCE to the 1st ce ...

, who lived in the Middle East from the 1st century BC to the 1st century AD, apparently shunned sex, marriage, and slavery. They also renounced wealth, lived communally, and were pacifist vegetarians. An Early Christian sect known as the Adamites existed in North Africa in the 2nd, 3rd and 4th centuries and rejected marriage. They practiced nudism and believed themselves to be without original sin.

In the 6th century, adherents of Mazdakism in pre-Muslim Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

apparently supported a kind of free love in the place of marriage. One folk story from the period that contains a mention of a free-love (and nudist) community under the sea is "The Tale of Abdullah the Fisherman and Abdullah the Merman" from ''The Book of One Thousand and One Nights

''One Thousand and One Nights'' ( ar, أَلْفُ لَيْلَةٍ وَلَيْلَةٌ, italic=yes, ) is a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the ''Arabian ...

'' (c. 10th–12th century).

Karl Kautsky

Karl Johann Kautsky (; ; 16 October 1854 – 17 October 1938) was a Czech-Austrian philosopher, journalist, and Marxist theorist. Kautsky was one of the most authoritative promulgators of orthodox Marxism after the death of Friedrich Engels i ...

, writing in 1895, noted that a number of "communistic" movements throughout the Middle Ages also rejected marriage. Typical of such movements, the Cathar

Catharism (; from the grc, καθαροί, katharoi, "the pure ones") was a Christian dualist or Gnostic movement between the 12th and 14th centuries which thrived in Southern Europe, particularly in northern Italy and southern France. Follo ...

s of 10th to 14th century Western Europe freed followers from all moral prohibition and religious obligation, but respected those who lived simply, avoided the taking of human or animal life, and were celibate. Women had an uncommon equality and autonomy, even as religious leaders. The Cathars and similar groups (the Waldenses, Apostle brothers, Beghards

The Beguines () and the Beghards () were Christian lay religious orders that were active in Western Europe, particularly in the Low Countries, in the 13th–16th centuries. Their members lived in semi-monastic communities but did not take forma ...

and Beguines

The Beguines () and the Beghards () were Christian lay religious orders that were active in Western Europe, particularly in the Low Countries, in the 13th–16th centuries. Their members lived in semi-monastic communities but did not take forma ...

, Lollards

Lollardy, also known as Lollardism or the Lollard movement, was a proto-Protestant Christian religious movement that existed from the mid-14th century until the 16th-century English Reformation. It was initially led by John Wycliffe, a Catholic ...

, and Hussites

The Hussites ( cs, Husité or ''Kališníci''; "Chalice People") were a Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement that followed the teachings of reformer Jan Hus, who became the best known representative of the Bohemian Reformation.

The Huss ...

) were branded as heretics

Heresy is any belief or theory that is strongly at variance with established beliefs or customs, in particular the accepted beliefs of a church or religious organization. The term is usually used in reference to violations of important religi ...

by the Roman Catholic Church and suppressed. Other movements shared their critique of marriage but advocated free sexual relations rather than celibacy, such as the Brethren of the Free Spirit, Taborite

The Taborites ( cs, Táborité, cs, singular Táborita), known by their enemies as the Picards, were a faction within the Hussite movement in the medieval Lands of the Bohemian Crown.

Although most of the Taborites were of rural origin, they ...

s, and Picards

The Taborites ( cs, Táborité, cs, singular Táborita), known by their enemies as the Picards, were a faction within the Hussite movement in the medieval Lands of the Bohemian Crown.

Although most of the Taborites were of rural origin, they ...

.

Enlightenment thought

The ideals of free love found their champion in one of the earliest English

The ideals of free love found their champion in one of the earliest English feminists

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism incorporates the position that society prioritizes the male poi ...

, Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft (, ; 27 April 1759 – 10 September 1797) was a British writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional personal relationsh ...

. In her writings, Wollstonecraft challenged the institution of marriage, and advocated its abolition. Her novels criticized the social construction of marriage and its effects on women. In her first novel, ''Mary: A Fiction'' written in 1788, the heroine is forced into a loveless marriage for economic reasons. She finds love in relationships with another man and a woman. The novel, ''Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman'', never finished but published in 1798, revolves around the story of a woman imprisoned in an asylum by her husband. Maria finds fulfilment outside of marriage, in an affair with a fellow inmate. Wollstonecraft makes it clear that "women had strong sexual desire

Sexual desire is an emotion and motivational state characterized by an interest in sexual objects or activities, or by a drive to seek out sexual objects or to engage in sexual activities. It is an aspect of sexuality, which varies significantly f ...

s and that it was degrading and immoral to pretend otherwise."

Wollstonecraft felt that women should not give up freedom and control of their sexuality, and thus did not marry her partner, Gilbert Imlay, despite the two conceiving and having a child together in the midst of the Terror of the French Revolution. Though the relationship ended badly, due in part to the discovery of Imlay's infidelity, and not least because Imlay abandoned her for good, Wollstonecraft's belief in free love survived. She later developed a relationship with the anarchist William Godwin, who shared her free love ideals, and published on the subject throughout his life. However, the two did decide to marry, just months before her death from complications in parturition

Birth is the act or process of bearing or bringing forth offspring, also referred to in technical contexts as parturition. In mammals, the process is initiated by hormones which cause the muscular walls of the uterus to contract, expelling the f ...

.

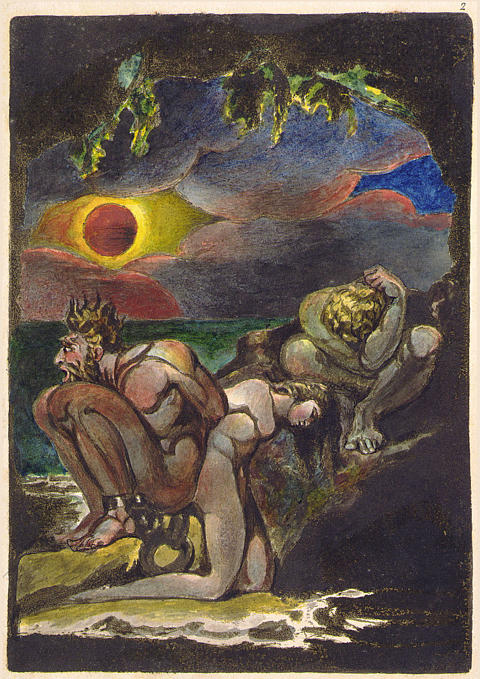

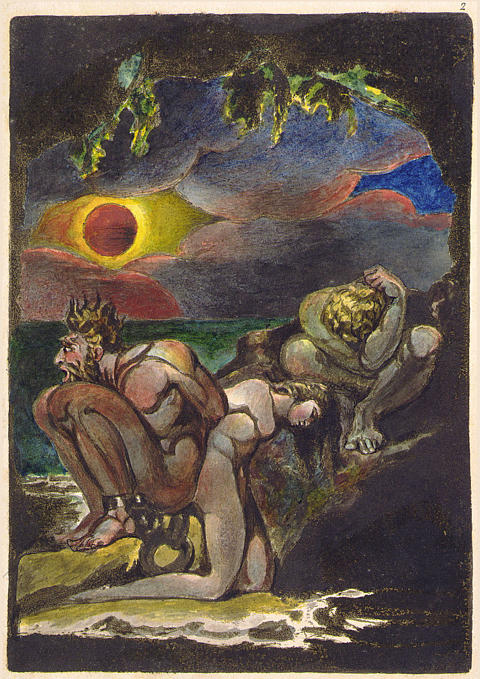

A member of Wollstonecraft's circle of notable radical intellectuals in England was the Romantic poet

A member of Wollstonecraft's circle of notable radical intellectuals in England was the Romantic poet William Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual art of the Romantic Age. ...

, who explicitly compared the sexual oppression of marriage to slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in works such as ''Visions of the Daughters of Albion'' (1793), published five years after Wollstonecraftr's ''Mary''. Blake was critical of the marriage laws of his day, and generally railed against traditional Christian notions of chastity

Chastity, also known as purity, is a virtue related to temperance. Someone who is ''chaste'' refrains either from sexual activity considered immoral or any sexual activity, according to their state of life. In some contexts, for example when ma ...

as a virtue. At a time of tremendous strain in his marriage, in part due to Catherine's apparent inability to bear children, he directly advocated bringing a second wife into the house. His poetry suggests that external demands for marital fidelity reduce love to mere duty rather than authentic affection, and decries jealousy and egotism as a motive for marriage laws. Poems such as "Why should I be bound to thee, O my lovely Myrtle-tree?" and "Earth's Answer" seem to advocate multiple sexual partners. In his poem "London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

" he speaks of "the Marriage-Hearse" plagued by "the youthful Harlot's curse", the result alternately of false Prudence and/or Harlotry. ''Visions of the Daughters of Albion'' is widely (though not universally) read as a tribute to free love since the relationship between Bromion and Oothoon is held together only by laws and not by love. For Blake, law and love are opposed, and he castigates the "frozen marriage-bed". In ''Visions'', Blake writes:

Blake believed that humans were "fallen", and that a major impediment to a free love society was corrupt human nature, not merely the intolerance of society and the jealousy of men, but the inauthentic hypocritical nature of human communication. He also seems to have thought that marriage should afford the joy of love, but that in reality it often does not, as a couple's knowledge of being chained often diminishes their joy.

In an act understood to support free love, the child of Wollstonecraft and Godwin, Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

, took up with the then still-married English romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in 1814 at the young age of sixteen. Shelley wrote in defence of free love in the prose notes of ''Queen Mab

Queen Mab is a fairy referred to in William Shakespeare's play ''Romeo and Juliet'', where "she is the fairies' midwife". Later, she appears in other poetry and literature, and in various guises in drama and cinema. In the play, her activity i ...

'' (1813), in his essay ''On Love'' (c. 1815), and in the poem ''Epipsychidion

''Epipsychidion'' is a major poetical work published in 1821 by Percy Bysshe Shelley. The work was subtitled: ''Verses addressed to the noble and unfortunate Lady Emilia V, now imprisoned in the convent of''. The title is Greek for "concerning ...

'' (1821).

Utopian socialism

Sharing the free-love ideals of the earlier social movements—as well as their feminism, pacifism, and simple communal life—were theutopian socialist

Utopian socialism is the term often used to describe the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet, and Robert Owen. Utopian socialism is often de ...

communities of early-nineteenth-century France and Britain, associated with writers and thinkers such as Henri de Saint-Simon

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon (17 October 1760 – 19 May 1825), often referred to as Henri de Saint-Simon (), was a French political, economic and socialist theorist and businessman whose thought had a substantial influence on p ...

and Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier (;; 7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of Fourier's social and moral views, held to be radical ...

in France, and Robert Owen in England. Fourier, who coined the term ''feminism,'' argued for true freedom, without suppressing passions: the suppression of passions is not only destructive to the individual, but to society as a whole. He argued that all sexual expressions should be enjoyed as long as people are not abused, and that "affirming one's difference" can actually enhance social integration.

Origins of the movement

The eminent sociologistHerbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism. Spencer originated the expression " survival of the fi ...

argued in his ''Principles of Sociology'' for the implementation of free divorce. Claiming that marriage consists of two components, "union by law" and "union by affection", he argued that with the loss of the latter union, legal union should lose all meaning and dissolve automatically, without the legal requirement for a divorce. Free love particularly stressed women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

since most sexual laws discriminated against women: for example, marriage laws and anti-birth control measures.

United States

John Humphrey Noyes

John Humphrey Noyes (September 3, 1811 – April 13, 1886) was an American preacher, radical religious philosopher, and utopian socialist. He founded the Putney, Oneida and Wallingford Communities, and is credited with coining the term "com ...

, although he preferred to use the term ' complex marriage'. Noyes founded the Oneida Community

The Oneida Community was a perfectionist religious communal society founded by John Humphrey Noyes and his followers in 1848 near Oneida, New York. The community believed that Jesus had already returned in AD 70, making it possible for the ...

in 1848, a utopian community that "ejected

Ejection or Eject may refer to:

* Ejection (sports), the act of officially removing someone from a game

* Eject (''Transformers''), a fictional character from ''The Transformers'' television series

* "Eject" (song), 1993 rap rock single by Sense ...

conventional marriage both as a form of legalism from which Christians should be free and as a selfish institution in which men exerted rights of ownership over women". He found scriptural justification: "In the resurrection they neither marry nor are given in marriage, but are like the angels in heaven" (Matt. 22:30). Noyes also supported eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior o ...

; and only certain people (including Noyes himself) were allowed to become parents. Another movement was established in Berlin Heights, Ohio

Berlin Heights is a village in Berlin Township, Erie County, Ohio, United States. The population was 714 at the 2010 census. It is part of the Sandusky, Ohio Metropolitan Statistical Area.

In the late 1850s a branch of the "free love" moveme ...

.

In 1852, a writer named Marx Edgeworth Lazarus

Marx Edgeworth Lazarus (February 6, 18221896) was an American individualist anarchist, Fourierist, and free-thinker. Lazarus was a practicing doctor of homeopathy who also wrote a number of books and articles, some under the pseudonym "Edgeworth" ...

published a tract entitled "Love vs. Marriage pt. 1", in which he portrayed marriage as "incompatible with social harmony and the root cause of mental and physical impairments." Lazarus intertwined his writings with his religious teachings, a factor that made the Christian community more tolerable to the free love idea. Elements of the free-love movement also had links to abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

movements, drawing parallels between slavery and " sexual slavery" (marriage), and forming alliances with black activists.

American feminist Victoria Woodhull

Victoria Claflin Woodhull, later Victoria Woodhull Martin (September 23, 1838 – June 9, 1927), was an American leader of the women's suffrage movement who ran for President of the United States in the 1872 election. While many historians ...

(1838–1927), the first woman to run for presidency in the U.S. in 1872, was also called "the high priestess of free love". In 1871, Woodhull wrote: "Yes, I am a Free Lover. I have an inalienable, constitutional and natural right to love whom I may, to love as long or as short a period as I can; to change that love every day if I please, and with that right neither you nor any law you can frame have any right to interfere".

The women's movement, free love and

The women's movement, free love and Spiritualism

Spiritualism is the metaphysical school of thought opposing physicalism and also is the category of all spiritual beliefs/views (in monism and Mind-body dualism, dualism) from ancient to modern. In the long nineteenth century, Spiritualism (w ...

were three strongly linked movements at the time, and Woodhull was also a spiritualist leader. Like Noyes, she also supported eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior o ...

. Fellow social reformer and educator Mary Gove Nichols was happily married (to her second husband), and together they published a newspaper and wrote medical books and articles. Both Woodhull and Nichols eventually repudiated free love.

Publications of the movement in the second half of the 19th century included Nichols' Monthly, ''The Social Revolutionist'', '' Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly'' (ed. Victoria Woodhull and her sister Tennessee Claflin), '' The Word'' (ed. Ezra Heywood

Ezra Hervey Heywood (; September 29, 1829 – May 22, 1893) was an American individualist anarchist, slavery abolitionist, and advocate of equal rights for women.

Philosophy

Heywood saw what he believed to be a disproportionate concentration of ...

), ''Lucifer, the Light-Bearer

Moses Harman (October 12, 1830January 30, 1910) was an American schoolteacher and publisher notable for his staunch support for women's rights. He was prosecuted under the Comstock Law for content published in his anarchist periodical ''Lucifer ...

'' (ed. Moses Harman

Moses Harman (October 12, 1830January 30, 1910) was an American schoolteacher and publisher notable for his staunch support for women's rights. He was prosecuted under the Comstock Law for content published in his anarchist periodical ''Lucifer ...

) and the German-language Detroit newspaper ''Der Arme Teufel'' (ed. Robert Reitzel). Organisations included the New England Free Love League, founded with the assistance of American libertarian socialist Benjamin Tucker

Benjamin Ricketson Tucker (; April 17, 1854 – June 22, 1939) was an American individualist anarchist and libertarian socialist.Martin, James J. (1953)''Men Against the State: The Expositers of Individualist Anarchism in America, 1827–1908''< ...

as a spin-off from the New England Labor Reform League (NELRL). A minority of freethinkers

Freethought (sometimes spelled free thought) is an epistemological viewpoint which holds that beliefs should not be formed on the basis of authority, tradition, revelation, or dogma, and that beliefs should instead be reached by other methods ...

also supported free love.

The most radical free love journal was ''The Social Revolutionist'', published in the 1856–1857, by John Patterson. The first volume consisted of twenty writers, of which only one was a woman.

Sex radicals were not alone in their fight against marriage ideals. Some other nineteenth-century Americans saw this social institution as flawed, but hesitated to abolish it. Groups such as the Shakers, the Oneida Community, and the Latter-day Saints were wary of the social notion of marriage. These organizations and sex radicals believed that true equality would never exist between the sexes as long as the church and the state continued to work together, worsening the problem of subordination of wives to their husbands.

Free-love movements continued into the early 20th century in bohemian circles in New York's Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

. A group of Villagers lived free-love ideals and promoted them in the political journal ''The Masses

''The Masses'' was a graphically innovative magazine of socialist politics published monthly in the United States from 1911 until 1917, when federal prosecutors brought charges against its editors for conspiring to obstruct conscription. It was ...

'' and its sister publication '' The Little Review,'' a literary journal. Incorporating influences from the writings of the English thinkers and activists Edward Carpenter

Edward Carpenter (29 August 1844 – 28 June 1929) was an English utopian socialist, poet, philosopher, anthologist, an early activist for gay rightsWarren Allen Smith: ''Who's Who in Hell, A Handbook and International Directory for Human ...

and Havelock Ellis

Henry Havelock Ellis (2 February 1859 – 8 July 1939) was an English physician, eugenicist, writer, progressive intellectual and social reformer who studied human sexuality. He co-wrote the first medical textbook in English on homosexuality i ...

, women such as Emma Goldman campaigned for a range of sexual freedoms, including homosexuality and access to contraception. Other notable figures among the Greenwich-Village scene who have been associated with free love include Edna St. Vincent Millay, Max Eastman

Max Forrester Eastman (January 4, 1883 – March 25, 1969) was an American writer on literature, philosophy and society, a poet and a prominent political activist. Moving to New York City for graduate school, Eastman became involved with radical ...

, Crystal Eastman, Floyd Dell

Floyd James Dell (June 28, 1887 – July 23, 1969) was an American newspaper and magazine editor, literary critic, novelist, playwright, and poet. Dell has been called "one of the most flamboyant, versatile and influential American Men of Letters ...

, Mabel Dodge Luhan

Mabel Evans Dodge Sterne Luhan (pronounced ''LOO-hahn''; née Ganson; February 26, 1879 – August 13, 1962) was a wealthy American patron of the arts, who was particularly associated with the Taos art colony.

Early life

Mabel Ganson was the heir ...

, Ida Rauh, Hutchins Hapgood

Hutchins Harry Hapgood (1869–1944) was an American journalist, author and anarchist.

Life and career

Hapgood was born to Charles Hutchins Hapgood (1836–1917) and Fanny Louise (Powers) Hapgood (1846–1922) and grew up in Alton, Illinois, ...

, and Neith Boyce

Neith Boyce (March 21, 1872 – December 2, 1951) was an American novelist, journalist, and theatre artist. Much of Boyce’s earlier work was published with help from her parents, Mary and Henry Harrison Boyce. Neith Boyce later co-founded the ...

. Dorothy Day

Dorothy Day (November 8, 1897 – November 29, 1980) was an American journalist, social activist and anarchist who, after a bohemian youth, became a Catholic without abandoning her social and anarchist activism. She was perhaps the best-known ...

also wrote passionately in defense of free love, women's rights, and contraception—but later, after converting to Catholicism, she criticized the sexual revolution of the sixties.

The development of the idea of free love in the United States was also significantly impacted by the publisher of ''Playboy

''Playboy'' is an American men's lifestyle and entertainment magazine, formerly in print and currently online. It was founded in Chicago in 1953, by Hugh Hefner and his associates, and funded in part by a $1,000 loan from Hefner's mother.

K ...

'' magazine, Hugh Hefner

Hugh Marston Hefner (April 9, 1926 – September 27, 2017) was an American magazine publisher. He was the founder and editor-in-chief of ''Playboy'' magazine, a publication with revealing photographs and articles which provoked charges of obsc ...

, whose activities and persona over more than a half century popularized the idea of free love to some of the general public.

United Kingdom

Free love was a central tenet of the philosophy of theFellowship of the New Life

The Fellowship of the New Life was a British organisation in the 19th century, most famous for a splinter group, the Fabian Society.

It was founded in 1883, by the Scottish intellectual Thomas Davidson. Fellowship members included the poet Edwa ...

, founded in 1883, by the Scottish intellectual Thomas Davidson. Fellowship members included many illustrious intellectuals of the day, who went on to radically challenge accepted Victorian notions of morality and sexuality, including poets Edward Carpenter

Edward Carpenter (29 August 1844 – 28 June 1929) was an English utopian socialist, poet, philosopher, anthologist, an early activist for gay rightsWarren Allen Smith: ''Who's Who in Hell, A Handbook and International Directory for Human ...

and John Davidson, animal rights activist Henry Stephens Salt

Henry Shakespear Stephens Salt (; 20 September 1851 – 19 April 1939) was an English writer and campaigner for social reform in the fields of prisons, schools, economic institutions, and the treatment of animals. He was a noted ethical vegeta ...

, sexologist Havelock Ellis

Henry Havelock Ellis (2 February 1859 – 8 July 1939) was an English physician, eugenicist, writer, progressive intellectual and social reformer who studied human sexuality. He co-wrote the first medical textbook in English on homosexuality i ...

, feminists Edith Lees, Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst ('' née'' Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was an English political activist who organised the UK suffragette movement and helped women win the right to vote. In 1999, ''Time'' named her as one of the 100 Most Impo ...

and Annie Besant

Annie Besant ( Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was a British socialist, theosophist, freemason, women's rights activist, educationist, writer, orator, political party member and philanthropist.

Regarded as a champion of human f ...

and writers H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells"Wells, H. G."

Revised 18 May 2015. '' The best-known British advocate of free love was the philosopher

The best-known British advocate of free love was the philosopher

An important propagandist of free love was individualist anarchist

An important propagandist of free love was individualist anarchist

Retrieved 10 June 2010 He wrote many propagandist articles on this subject such as "De la liberté sexuelle" (1907) where he advocated not only a vague free love but also multiple partners, which he called "plural love". In the individualist anarchist journal ''L'en dehors'' he and others continued in this way. Armand seized this opportunity to outline his theses supporting revolutionary sexualism and camaraderie amoureuse that differed from the traditional views of the partisans of free love in several respects. Later Armand submitted that from an individualist perspective nothing was reprehensible about making "love", even if one did not have very strong feelings for one's partner. "The camaraderie amoureuse thesis", he explained, "entails a free contract of association (that may be annulled without notice, following prior agreement) reached between anarchist individualists of different genders, adhering to the necessary standards of sexual hygiene, with a view toward protecting the other parties to the contract from certain risks of the amorous experience, such as rejection, rupture, exclusivism, possessiveness, unicity, coquetry, whims, indifference, flirtatiousness, disregard for others, and prostitution." He also published ''Le Combat contre la jalousie et le sexualisme révolutionnaire'' (1926), followed over the years by ''Ce que nous entendons par liberté de l'amour'' (1928), ''La Camaraderie amoureuse ou "chiennerie sexuelle"'' (1930), and, finally, ''La Révolution sexuelle et la camaraderie amoureuse'' (1934), a book of nearly 350 pages comprising most of his writings on sexuality. In a text from 1937, he mentioned among the individualist objectives the practice of forming

A more extensive quote from Lenin follows: "It seems to me that this superabundance of sex theories ... springs from the desire to justify one's own abnormal or excessive sex life before bourgeois morality and to plead for tolerance towards oneself. This veiled respect for bourgeois morality is as repugnant to me as rooting about in all that bears on sex. No matter how rebellious and revolutionary it may be made to appear, it is in the final analysis thoroughly bourgeois. It is, mainly, a hobby of the intellectuals and of the sections nearest to them. There is no place for it in the party, in the class-conscious, fighting proletariat." Zetkin also recounted Lenin's denunciation of plans to organise Hamburg's women prostitutes into a "special revolutionary militant section": he saw this as "corrupt and degenerate". Despite the traditional marital lives of Lenin and most Bolsheviks, they believed that sexual relations were outside the jurisdiction of the state. The Soviet government abolished centuries-old Czarist regulations on personal life, which had prohibited homosexuality and made it difficult for women to obtain divorce permits or to live singly. However, by the end of the 1920s,

PBS.org, Accessed 26 April 2014 Many among the counterculture youth sided with New Left arguments that marriage was a symbol of the traditional capitalist culture which supported war. " Make Love Not War" became a popular slogan in the counterculture movement which denounced both war and capitalism. Images from the pro-socialist May 1968 uprising in France, which occurred as the

"The recurring movements of free love" by Saskia Poldervaart

* Victoria Woodhull, ''Free Lover: Sex, Marriage And Eugenics in the Early Speeches of Victoria Woodhull'', Seattle: Inkling, 2005, * Stoehr, Taylor, ed. ''Free Love in America: A Documentary History'', New York: AMS Press, 1977 * Sears, Hal, ''The Sex Radicals: Free Love in High Victorian America'', Lawrence, KS: The Regents Press of Kansas, 1977 * Spurlock, John ''Free Love: Marriage and Middle Class Radicalism, 1825–1860'', New York: New York University Press, 1987 * Joanne E. Passet, ''Sex Radicals and the Quest for Women's Equality'', Champaign:

"Emile Armand and la camaraderie amourouse. Revolutionary sexualism and the struggle against jealousy." by Francis Rousin

* Barbara Goldsmith, ''Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism, and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull'', 1999, * Goldman, Emma,

Marriage and Love

', New York: Mother Earth Publishing Association, 1911 * Françoise Basch, ''Rebelles américaines au XIXe siècle : marriage, amour libre et politique'', Paris : Méridiens Klincksieck, 1990 * Curt von Westernhagen, ''Wagner'', Cambridge, 1978, . {{DEFAULTSORT:Free Love Hippie movement Love Sexual revolution

Revised 18 May 2015. ''

Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

, Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, ...

and Olive Schreiner

Olive Schreiner (24 March 1855 – 11 December 1920) was a South African author, anti-war campaigner and intellectual. She is best remembered today for her novel ''The Story of an African Farm'' (1883), which has been highly acclaimed. It deal ...

. Its objective was "The cultivation of a perfect character in each and all," and believed in the transformation of society through setting an example of clean simplified living for others to follow. Many of the Fellowship's members advocated pacifism

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

, vegetarianism

Vegetarianism is the practice of abstaining from the consumption of meat (red meat, poultry, seafood, insects, and the flesh of any other animal). It may also include abstaining from eating all by-products of animal slaughter.

Vegetarianism may ...

and simple living

Simple living refers to practices that promote simplicity in one's lifestyle. Common practices of simple living include reducing the number of possessions one owns, depending less on technology and services, and spending less money. Not only is ...

.

Edward Carpenter

Edward Carpenter (29 August 1844 – 28 June 1929) was an English utopian socialist, poet, philosopher, anthologist, an early activist for gay rightsWarren Allen Smith: ''Who's Who in Hell, A Handbook and International Directory for Human ...

was the first activist for the rights of homosexual

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to peop ...

s. He became interested in progressive education, especially providing information to young people on the topic of sexual education. For Carpenter, sexual education meant forwarding a clear analysis of the ways in which sex and gender were used to oppress women, contained in Carpenter's radical work ''Love's Coming-of-Age''. In it he argued that a just and equal society must promote the sexual and economic freedom

Economic freedom, or economic liberty, is the ability of people of a society to take economic actions. This is a term used in economic and policy debates as well as in the philosophy of economics. One approach to economic freedom comes from the l ...

of women. The main crux of his analysis centred on the negative effects of the institution of marriage. He regarded marriage in England as both enforced celibacy and a form of prostitution.

The best-known British advocate of free love was the philosopher

The best-known British advocate of free love was the philosopher Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, ...

, later Third Earl Russell, who said that he did not believe he really knew a woman until he had made love with her. Russell consistently addressed aspects of free love throughout his voluminous writings, and was not personally content with conventional monogamy

Monogamy ( ) is a form of dyadic relationship in which an individual has only one partner during their lifetime. Alternately, only one partner at any one time (serial monogamy) — as compared to the various forms of non-monogamy (e.g., polyga ...

until extreme old age. His most famous work on the subject was ''Marriage and Morals

''Marriage and Morals'' is a 1929 book by philosopher Bertrand Russell, in which the author questions the Victorian notions of morality regarding sex and marriage.

Russell argues that the laws and ideas about sex of his time were a potpourri fr ...

'', published in 1929. The book heavily criticizes the Victorian notions of morality regarding sex and marriage. Russell argued that the laws and ideas about sex of his time were a potpourri from various sources, which were no longer valid with the advent of contraception

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent unwanted pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth contr ...

, as the sexual acts are now separated from the conception. He argued that family is most important for the welfare of children, and as such, a man and a woman should be considered bound only after her first pregnancy.

''Marriage and Morals'' prompted vigorous protests and denunciations against Russell shortly after the book's publication. A decade later, the book cost him his professorial appointment at the City College of New York

The City College of the City University of New York (also known as the City College of New York, or simply City College or CCNY) is a public university within the City University of New York (CUNY) system in New York City. Founded in 1847, Cit ...

due to a court judgment that his opinions made him "morally unfit" to teach. Contrary to what many people believed, Russell did not advocate an extreme libertine position. Instead, he felt that sex, although a natural impulse like hunger or thirst, involves more than that, because no one is "satisfied by the bare sexual act". He argued that abstinence enhances the pleasure of sex, which is better when it "has a large psychical element than when it is purely physical".

Russell noted that for a marriage to work requires that there "be a feeling of complete equality on both sides; there must be no interference with mutual freedom; there must be the most complete physical and mental intimacy; and there must be a certain similarity in regard to standards of value". He argued that it was, in general, impossible to sustain this mutual feeling for an indefinite length of time, and that the only option in such a case was to provide for either the easy availability of divorce

Divorce (also known as dissolution of marriage) is the process of terminating a marriage or marital union. Divorce usually entails the canceling or reorganizing of the legal duties and responsibilities of marriage, thus dissolving the ...

, or the social sanction of extra-marital sex.

Russell's view on marriage changed as he went through personal struggles of subsequent marriages, in his autobiography he writes: "I do not know what I think now about the subject of marriage. There seem to be insuperable objections to every general theory about it. Perhaps easy divorce causes less unhappiness than any other system, but I am no longer capable of being dogmatic on the subject of marriage ".

Russell was also a very early advocate of repealing sodomy laws.

France

An important propagandist of free love was individualist anarchist

An important propagandist of free love was individualist anarchist Émile Armand

Émile Armand (26 March 1872 – 19 February 1962), pseudonym of Ernest-Lucien Juin Armand, was an influential French individualist anarchist at the beginning of the 20th century and also a dedicated free love/polyamory, intentional community, a ...

. He advocated naturism

Naturism is a lifestyle of practising non-sexual social nudity in private and in public; the word also refers to the cultural movement which advocates and defends that lifestyle. Both may alternatively be called nudism. Though the two terms ar ...

and polyamory

Polyamory () is the practice of, or desire for, romantic relationships with more than one partner at the same time, with the informed consent of all partners involved. People who identify as polyamorous may believe in open relationships wit ...

in what he termed ''la camaraderie amoureuse''."Emile Armand and la camaraderie amourouse – Revolutionary sexualism and the struggle against jealousy." by Francis RousinRetrieved 10 June 2010 He wrote many propagandist articles on this subject such as "De la liberté sexuelle" (1907) where he advocated not only a vague free love but also multiple partners, which he called "plural love". In the individualist anarchist journal ''L'en dehors'' he and others continued in this way. Armand seized this opportunity to outline his theses supporting revolutionary sexualism and camaraderie amoureuse that differed from the traditional views of the partisans of free love in several respects. Later Armand submitted that from an individualist perspective nothing was reprehensible about making "love", even if one did not have very strong feelings for one's partner. "The camaraderie amoureuse thesis", he explained, "entails a free contract of association (that may be annulled without notice, following prior agreement) reached between anarchist individualists of different genders, adhering to the necessary standards of sexual hygiene, with a view toward protecting the other parties to the contract from certain risks of the amorous experience, such as rejection, rupture, exclusivism, possessiveness, unicity, coquetry, whims, indifference, flirtatiousness, disregard for others, and prostitution." He also published ''Le Combat contre la jalousie et le sexualisme révolutionnaire'' (1926), followed over the years by ''Ce que nous entendons par liberté de l'amour'' (1928), ''La Camaraderie amoureuse ou "chiennerie sexuelle"'' (1930), and, finally, ''La Révolution sexuelle et la camaraderie amoureuse'' (1934), a book of nearly 350 pages comprising most of his writings on sexuality. In a text from 1937, he mentioned among the individualist objectives the practice of forming

voluntary association

A voluntary group or union (also sometimes called a voluntary organization, common-interest association, association, or society) is a group of individuals who enter into an agreement, usually as volunteering, volunteers, to form a body (or organ ...

s for purely sexual purposes of heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual nature or of a combination thereof.

He also supported the right of individuals to change sex and stated his willingness to rehabilitate forbidden pleasures, non-conformist caresses (he was personally inclined toward voyeurism), as well as sodomy. This led him to allocate more and more space to what he called "the sexual non-conformists", while excluding physical violence. His militancy also included translating texts from people such as Alexandra Kollontai

Alexandra Mikhailovna Kollontai (russian: Алекса́ндра Миха́йловна Коллонта́й, née Domontovich, Домонто́вич; – 9 March 1952) was a Russian revolutionary, politician, diplomat and Marxist the ...

and Wilhelm Reich

Wilhelm Reich ( , ; 24 March 1897 – 3 November 1957) was an Austrian Doctor of Medicine, doctor of medicine and a psychoanalysis, psychoanalyst, along with being a member of the second generation of analysts after Sigmund Freud. The author ...

and establishments of free love associations which tried to put into practice ''la camaraderie amoureuse'' through actual sexual experiences.

Free love advocacy groups active during this time included the ''Association d'Études sexologiques'' and the ''Ligue mondiale pour la Réforme sexuelle sur une base scientifique''.

USSR

After theOctober Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

in Russia, Alexandra Kollontai

Alexandra Mikhailovna Kollontai (russian: Алекса́ндра Миха́йловна Коллонта́й, née Domontovich, Домонто́вич; – 9 March 1952) was a Russian revolutionary, politician, diplomat and Marxist the ...

became the most prominent woman in the Soviet administration. Kollontai was also a champion of free love. However, Clara Zetkin

Clara Zetkin (; ; ''née'' Eißner ; 5 July 1857 – 20 June 1933) was a German Marxist theorist, communist activist, and advocate for women's rights.

Until 1917, she was active in the Social Democratic Party of Germany. She then joined the ...

recorded that Lenin opposed free love as "completely un-Marxist, and moreover, anti-social".Zetkin, Clara, 1934, ''Lenin on the Woman Question,'' New York: International, p. 7. Published in ''Reminiscences of Lenin.''A more extensive quote from Lenin follows: "It seems to me that this superabundance of sex theories ... springs from the desire to justify one's own abnormal or excessive sex life before bourgeois morality and to plead for tolerance towards oneself. This veiled respect for bourgeois morality is as repugnant to me as rooting about in all that bears on sex. No matter how rebellious and revolutionary it may be made to appear, it is in the final analysis thoroughly bourgeois. It is, mainly, a hobby of the intellectuals and of the sections nearest to them. There is no place for it in the party, in the class-conscious, fighting proletariat." Zetkin also recounted Lenin's denunciation of plans to organise Hamburg's women prostitutes into a "special revolutionary militant section": he saw this as "corrupt and degenerate". Despite the traditional marital lives of Lenin and most Bolsheviks, they believed that sexual relations were outside the jurisdiction of the state. The Soviet government abolished centuries-old Czarist regulations on personal life, which had prohibited homosexuality and made it difficult for women to obtain divorce permits or to live singly. However, by the end of the 1920s,

Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

had taken over the Communist Party and begun to implement socially conservative policies. Homosexuality was classified as a mental disorder, and free love was further demonized.

Recent

With the Summer of Love in 1967, the eccentricities of thebeat generation

The Beat Generation was a literary subculture movement started by a group of authors whose work explored and influenced American culture and politics in the post-war era. The bulk of their work was published and popularized by Silent Generatio ...

became a nationally recognized movement. Despite the developing sexual revolution

The sexual revolution, also known as the sexual liberation, was a social movement that challenged traditional codes of behavior related to sexuality and interpersonal relationships throughout the United States and the developed world from the 1 ...

and the influence of the Beatniks had in this new counterculture

A counterculture is a culture whose values and norms of behavior differ substantially from those of mainstream society, sometimes diametrically opposed to mainstream cultural mores.Eric Donald Hirsch. ''The Dictionary of Cultural Literacy''. Hou ...

social rebellion, it has been acknowledged that the New Left movement was arguably the most prominent advocate of free love during the late 1960s.Emma Goldman:People & Events: Free LovePBS.org, Accessed 26 April 2014 Many among the counterculture youth sided with New Left arguments that marriage was a symbol of the traditional capitalist culture which supported war. " Make Love Not War" became a popular slogan in the counterculture movement which denounced both war and capitalism. Images from the pro-socialist May 1968 uprising in France, which occurred as the

anti-war

An anti-war movement (also ''antiwar'') is a social movement, usually in opposition to a particular nation's decision to start or carry on an armed conflict, unconditional of a maybe-existing just cause. The term anti-war can also refer to pa ...

protests were escalating throughout the United States, would provide a significant source of morale to the New Left cause as well.

Canadian Justice Minister, and future Prime Minister, Pierre Elliot Trudeau

Joseph Philippe Pierre Yves Elliott Trudeau ( , ; October 18, 1919 – September 28, 2000), also referred to by his initials PET, was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the 15th prime minister of Canada from 1968 to 1979 and ...

's 20 December 1967 statement "there's no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation" was a very public declaration justifying his government's decriminalization of sexual activity between same sex partners in Canada, following 1967's Summer of Love.

See also

Notes

References

Further reading

"The recurring movements of free love" by Saskia Poldervaart

* Victoria Woodhull, ''Free Lover: Sex, Marriage And Eugenics in the Early Speeches of Victoria Woodhull'', Seattle: Inkling, 2005, * Stoehr, Taylor, ed. ''Free Love in America: A Documentary History'', New York: AMS Press, 1977 * Sears, Hal, ''The Sex Radicals: Free Love in High Victorian America'', Lawrence, KS: The Regents Press of Kansas, 1977 * Spurlock, John ''Free Love: Marriage and Middle Class Radicalism, 1825–1860'', New York: New York University Press, 1987 * Joanne E. Passet, ''Sex Radicals and the Quest for Women's Equality'', Champaign:

University of Illinois Press

The University of Illinois Press (UIP) is an American university press and is part of the University of Illinois system. Founded in 1918, the press publishes some 120 new books each year, plus 33 scholarly journals, and several electronic project ...

, 2003,

* Martin Blatt, ''Free Love and Anarchism: The Biography of Ezra Heywood'', Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989

"Emile Armand and la camaraderie amourouse. Revolutionary sexualism and the struggle against jealousy." by Francis Rousin

* Barbara Goldsmith, ''Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism, and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull'', 1999, * Goldman, Emma,

Marriage and Love

', New York: Mother Earth Publishing Association, 1911 * Françoise Basch, ''Rebelles américaines au XIXe siècle : marriage, amour libre et politique'', Paris : Méridiens Klincksieck, 1990 * Curt von Westernhagen, ''Wagner'', Cambridge, 1978, . {{DEFAULTSORT:Free Love Hippie movement Love Sexual revolution